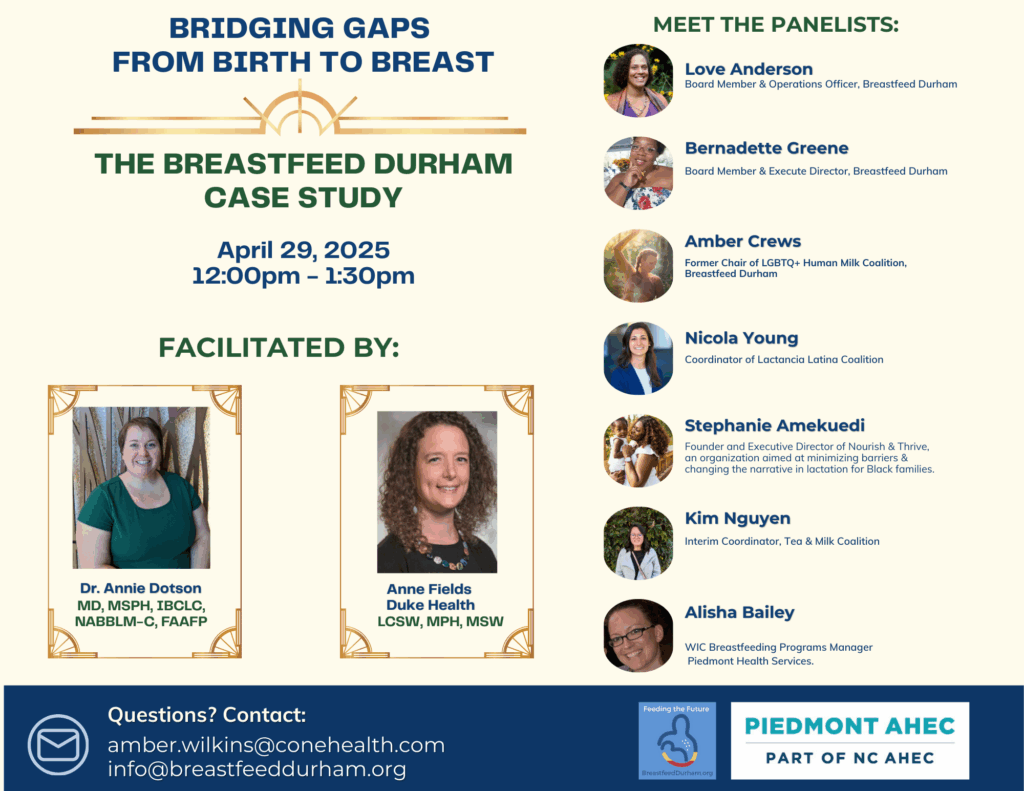

In April 2025, a powerful virtual gathering brought together lactation consultants, peer supporters, WIC leaders, physicians, policy advocates, and parents to discuss how to implement Step 6 of the Ten Steps to a Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community: Ensure access to culturally and linguistically appropriate lactation support. The panel was hosted by Piedmont AHEC with support from the Durham County Department of Public Health. The conversation centered on Durham, North Carolina, using the work of Breastfeed Durham as a case study for what change looks like on the ground.

Bridging Gaps in Lactation Support: Implementing Step 6 with Breastfeed Durham

In communities across the country, the promise of equitable breastfeeding support too often falls short. Families encounter barriers based on language, identity, systemic neglect, and limited access to culturally relevant care. That’s why Step 6 of the Ten Steps to a Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community—ensuring access to culturally and linguistically appropriate lactation support—is not just a checkbox, but a lifeline. And no community has worked harder to model this than Breastfeed Durham.

From Isolation to Infrastructure

Seven years ago, Durham had only two La Leche League meetings and little racial, cultural, or linguistic diversity in its lactation support network. Families—especially Black, Latinx, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, and immigrant families—were left out of mainstream resources. Peer-to-peer support was minimal, and driving to neighboring counties for care was the norm. Then came a pivot: instead of asking tired parents to do more, Breastfeed Durham asked systems to step up. Anchored in the 10 Steps framework, the team set out to center communities most often ignored—first Black families, and then expanding to Spanish-speaking, queer, Asian, and Indigenous families.

An In-Depth Reflection on the 2025 First Food Equity Series Panel

Below is a recap of the panel in a Q&A format, capturing both the content and the emotional momentum of the event.

Q: What are the most significant barriers to culturally appropriate lactation support in Durham?

Niki Young, medical student and lactation consultant: “Language is a major barrier. Even when interpreters are available, it creates an awkward dynamic. Many Spanish-speaking parents feel less inclined to ask questions or seek clarification. There is also a myth in some cultures that breastfeeding is supposed to hurt. Without culturally competent support, families give up before they get the help they need.”

Amber Crews, La Leche League leader and queer lactation advocate: “For LGBTQ families, it’s not about language; it’s about safety. Will this provider respect my pronouns? Will they understand that my trans husband is lactating, or that I’ve had top surgery but still have mammary glands? Queer families are often navigating care in systems that assume heteronormativity.”

Love Anderson, co-founder of Breastfeed Durham: “Seven years ago, Durham had only two La Leche League meetings and almost no racial or cultural diversity in lactation spaces. I remember just wanting to see a brown nipple in a support group. We asked ourselves: What if instead of expecting exhausted parents to do more, we asked systems to do more?”

Q: What are successful examples of implementing Step 6?

Stephanie Amekuedi, founder of Nourish & Thrive: “Breastfeed Durham stands out as a model. They’re working with hospitals, public health, and peer support groups to ensure that lactation support isn’t a luxury—it’s accessible to everyone. At Nourish & Thrive, we offer free prenatal and postnatal lactation classes because too many Black families are priced out of that kind of education.”

Kim Nguyen, WIC Assistant Manager at Piedmont Health: “We work with diverse populations, including Burmese and other refugee communities. Through Breastfeed Durham’s Tea and Milk Coalition, I was able to connect with national partners to source translated materials. That connection never would have happened without Step 6 work.”

Love Anderson: “We created new affinity groups: the Tea and Milk Coalition for Asian and Middle Eastern families, the Lactancia Latina Coalition for Spanish-speaking families, the LGBTQ+ Lactation Support Network, and the Black Breastfeeding Coalition. Every step we took toward equity revealed more gaps—and more need to listen.”

Q: How has peer-to-peer support changed the landscape?

Amber Crews: “Le Leche League saved my parenting life. But even today, some counties have one or two leaders at most. Wake County had several and now has one. Durham is lucky to have 10 active leaders. The pandemic hurt in-person support, and we’re still rebuilding.”

Love Anderson: “When I first started, my mother-in-law encouraged me to go to four peer meetings during pregnancy. I went grudgingly. But when I gave birth and felt completely lost, those meetings saved me. That model—peer support with cultural alignment and emotional safety—is still the gold standard.”

Stephanie Amekuedi: “Volunteers are the backbone. You don’t have to give 10 hours a week. One email saying, ‘Hey, a link on your website is broken’ can help a parent get the support they need.”

Q: Where are the remaining gaps in Step 6 implementation?

Alisha Bailey, WIC and Breastfeeding Program Manager, Piedmont Health: “We still need stronger referral pipelines between hospitals and community support. There are La Leche League leaders in our service area I’ve never met. That means we’re missing opportunities to refer WIC families to free peer support.”

Asia (Western NC SLP): “As a speech therapist working with NICU grads, I see so many families who were never told that their medically fragile babies could receive human milk. They leave the hospital full of grief and confusion.”

Jess Woon, RN, IBCLC: “Hospitals are still understaffed. Many staff don’t get lactation training. There’s often no time or incentive to connect families to community support, especially in NICUs. We need better collaboration between hospitals and people on the ground.”

Q: What can individuals do to support Step 6 work?

Amber Crews: “Start by gathering resources. We built a national list of LGBTQ-affirming lactation resources from scratch. Now it gets shared across the country. It started with just three people.”

Alisha Bailey: “Progress happens at the speed of relationships. Reach out to someone. Introduce yourself. Suggest a collaboration. The worst someone can say is ‘no.'”

Stephanie Amekuedi: “Speak up, but listen first. Don’t assume you know what people need. Ask. Then act.”

Conclusion: A Living Model

Breastfeed Durham shows that implementing Step 6 is not a one-time achievement—it’s a continuous cycle of listening, creating, and revising. Each new coalition, resource list, or support group arose because someone pointed out a gap. And every success story traces back to a volunteer, a peer, a parent, or a health worker who refused to let someone fall through the cracks.

For communities wondering where to begin, the answer is simple: start with one conversation, one coalition, one step. Because the work of equity is not about perfection—it’s about persistence.