In the face of North Carolina’s alarming syphilis surge, our community stands at a crucial crossroads. As advocates and providers, the responsibility to navigate the complexities of lactation support amidst this epidemic weighs heavily on us. There is a path forward. In this article, Brandyn Brown-White, a 2nd year MPH student in the Department of Maternal, Child, and Family Health and UNC Chapel Hill Gillings School of Global Public Health and MRTTI-IBCLC student merges science with compassion to safeguard our most vulnerable.

What Is Syphilis?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), syphilis is a curable, sexually transmitted (bacterial) infection that if not properly treated, may cause severe health complications. This infection is spread through direct contact with a sore during vaginal, anal, or oral sex and developed in four stages – primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary. Syphilis can spread from a pregnant person to their unborn baby, this is known as congenital syphilis. Congenital syphilis can complicate a pregnancy and cause serious issues for both the birthing person and the developing baby. Though this is true, it is typically preventable with early detection and immediate intervention. This can be achieved by receiving regular medical care while pregnant. All North Carolina healthcare providers are required to screen all pregnant people for syphilis at their first prenatal visit, sometimes between 28-30 weeks gestation, and at delivery. If a person does contract syphilis while pregnant, it can be treated with antibiotics that are safe to ingest during pregnancy. Despite being nestled in Durham, North Carolina’s city of medicine, many of the families we work with are still facing maternity care deserts, our community grapples with the challenge of ensuring equitable access to prenatal care, exacerbated by long wait times, the enduring effects of poverty, racism, and the multifaceted stresses burdening historically marginalized populations. If left untreated though, congenital syphilis can lead to premature birth, developmental challenges, and other issues. Such issues may be observed immediately at birth, while others may not present themselves for months or even years. In extreme cases, this condition can lead to infant death and stillbirth.

Where We Are Today

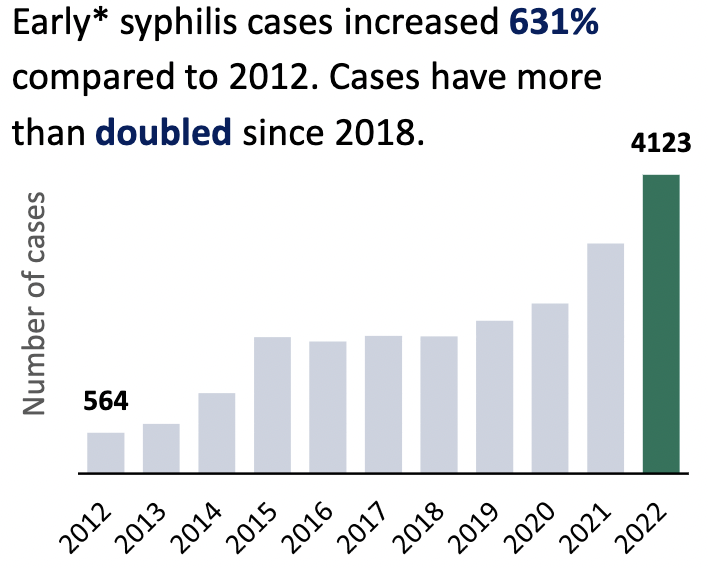

Since 2012, North Carolina has seen a 631% increase in known syphilis cases among adults aged 18 and over. Rates of congenital syphilis have also risen in our state. From 2017 to 2021, congenital syphilis rates rose 68%. Even more, one case of congenital syphilis was reported in 2012, compared to the 57 reported cases in 2022, and by the end of 2023, five stillbirths and two neonatal deaths due to congenital syphilis had been documented. This report showcases a steep increase from 2022, which reported no stillbirths or neonatal deaths as a result of this infection. The increase in syphilis and congenital syphilis acquisition rates paired with their potential implications if not immediately and properly treated, emphasizes the importance of not only safe sex, but also regular testing even while pregnant, and immediate treatment if infected.

Implications for Breastfeeding Families: Feeding and Treatment

Syphilis infection can spread to any part of your breast – including the nipple and areola. Because of this, there can be a lot of trepidation, uncertainty, and nervousness associated with breastfeeding while having syphilis. However, breastfeeding if you have syphilis is still possible. You can breastfeed (or continue to) as long as your baby and/or pumping parts do not touch a sore. If sores are present on your breast (but not necessarily the nipple or areola), the National Institutes of Health recommends pumping and/or hand-expressing the breast with sores until they heal. Doing this helps to maintain your milk supply and prevent painful engorgement due to extreme fullness without emptying. This pumped or expressed milk is safe and can be stored and provided to your baby. If any part of your breast pump contacts sores (like if a sore is present directly on your nipple and/or areola) while pumping though, the resulting milk should be thrown away and is not safe for your baby to consume. Treatment for syphilis while breastfeeding is also safe. Penicillin is the most common treatment for this infection and can be used while breastfeeding as long as you and/or your baby are not allergic to it. Even with this information provided, it is always recommended to check in with and work alongside your physician and child’s pediatrician. This will ensure that a plan for you and your family’s specific needs can be uniquely crafted and discussed for the benefit of everyone’s goals and desires.

Considerations When Informal Milk Sharing

Though breastmilk is regarded as the gold standard compared to formula, when considering informal or community milk sharing it is important to keep in mind that it can be difficult to know for sure that a donor’s milk is 100% safe. When acquiring donor milk from a milk bank, you can trust that all donors are screened, milk is tested, and pasteurization is completed to kill any harmful bacteria or viruses. This substantially reduces risks associated with breastmilk sharing. However, these steps cannot be ensured when going the informal route. It can be hard to know that a donor’s health and lifestyle are safe for the needs of your baby. Viruses and infections can potentially be passed to your baby via breast milk and result in potentially negative outcomes for your infant. Because of this, when considering peer-to-peer, informal, or community milk sharing, it is important to one, consult your healthcare provider, and two, minimize the risks as best you can.

Minimizing the Risks when Informal Milk Sharing

- Get to know your donor: learn about their health and daily lifestyle as much as possible.

- Obtain your donor’s blood work: see your donor’s blood test results and ensure they are recent and have been reviewed by a trusted healthcare professional.

- Limit the number of donors you use.

- Keep in touch with the donor.

- Work alongside the donor to ensure the milk you are receiving has been handled, stored, and transported accurately to best ensure the safety of your baby.

- Always consult your healthcare provider.

References

- https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm

- https://www.dph.ncdhhs.gov/epidemiology/communicable-disease/syphilis/rates

- https://www.axios.com/local/charlotte/2024/02/07/syphilis-cases-surge-north-carolina

- https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/blog/2023/12/15/nc-medicaid-and-public-health-joint-statement-congenital-syphilis

- https://www.cdc.gov/std/dstdp/sti-funding-at-work/jurisdictional-spotlights/northcarolina.pdf

- https://orwh.od.nih.gov/research/maternal-morbidity-and-mortality/information-for-women/sexually-transmitted-infections

- https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/syphilis

- https://mothertobaby.org/fact-sheets/syphilis/