Every year during Black Maternal Health Week, we are called to remember the mothers and babies we’ve lost—and to take action to protect the ones we still have.

We live and work in Durham, North Carolina—the so-called “City of Medicine.” But despite our proximity to world-class medical institutions, Black families here face an alarming and preventable truth: Black women and babies are still dying at disproportionate rates. One of the most powerful interventions we have to change that trajectory is also one of the oldest—breastfeeding.

Over the past two years, we’ve heard concerning rumors that Duke Regional Hospital does NOT plan to renew its Baby-Friendly designation, and that Duke University Hospital does NOT intend to pursue this initiative. Additionally, we’ve received reports that staff members fear repercussions, including threats to their employment, should they choose to participate in our survey or community partner award.

This raises a critical question: What is so daunting about the questions we’re asking? Is there a concern about potential liability, similar to situations observed in hospitals elsewhere? For instance, recent legal cases have highlighted the risks associated with feeding medically fragile infants cow’s milk-based formulas, which have been linked to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a serious intestinal disease with high mortality rates.

We initiated this work because Black women and babies were, and continue to be, disproportionately affected by adverse health outcomes in our city. While we’ve made strides, the reluctance to engage fully with initiatives like the Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community designation hampers our collective progress.

Studies have consistently shown that premature infants fed formula instead of breast milk face a higher risk of developing NEC. Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition that primarily affects premature and medically fragile infants. It involves inflammation and bacterial invasion of the intestinal wall, which can lead to the death of intestinal tissue. In severe cases, the intestines can rupture, leading to overwhelming infection (sepsis) and death. NEC typically occurs in the first few weeks of life and is most common in infants who are born before 32 weeks of gestation or who weigh less than 5.5 pounds at birth.

This underscores the importance of promoting and supporting breastfeeding practices, especially in communities with significant Black and Brown populations, where health disparities are already pronounced. We acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of individual providers and clinics within the Duke system who have championed breastfeeding support. However, institutional commitment is crucial to creating a truly supportive environment for all families.

Breastfeeding saves lives. It reduces maternal and infant mortality, strengthens immune systems, lowers the risk of chronic disease, and protects mental health. Yet institutional barriers—especially in health care—continue to deny Black families the support they need to feed their babies safely and with dignity.

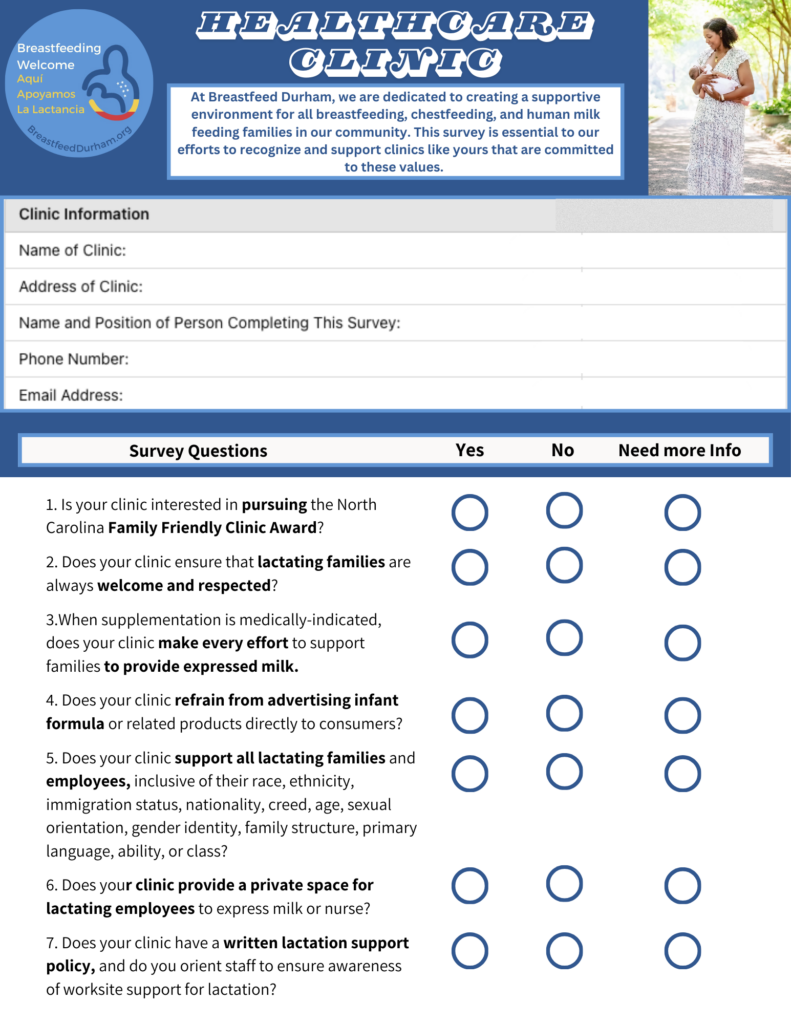

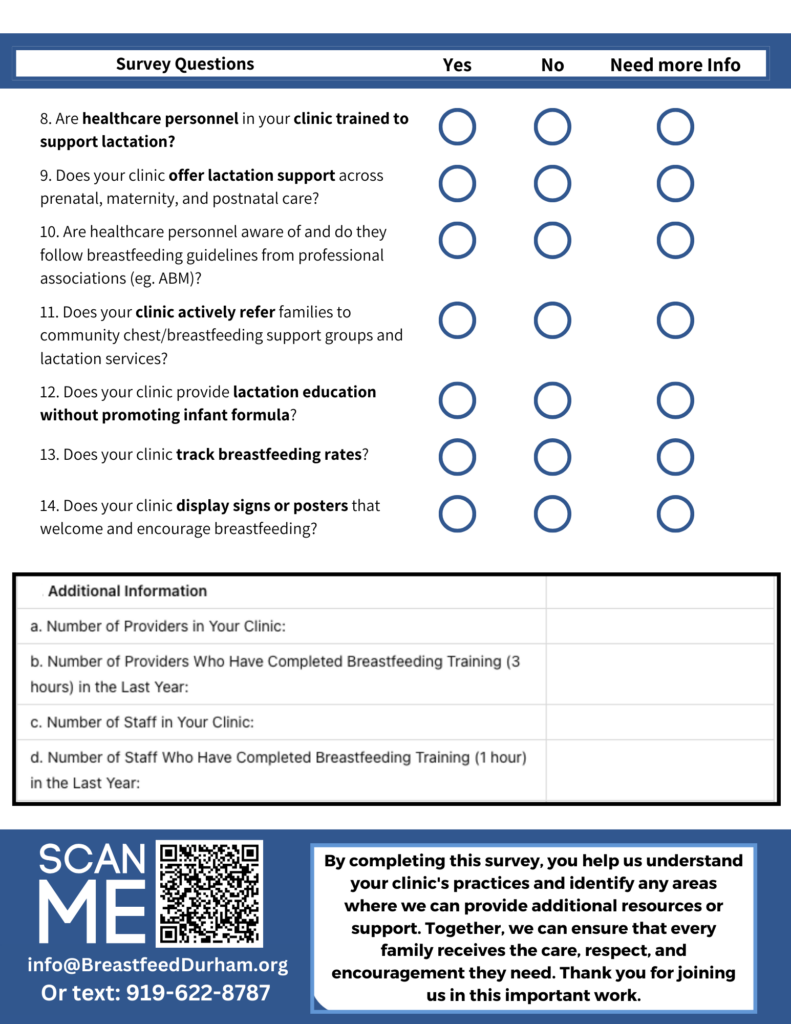

That’s why we launched the Ten Steps to a Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community, a public health initiative rooted in equity, accountability, and care. These Ten Steps are not aspirational—they are achievable, evidence-based benchmarks that ensure every family has access to consistent lactation support in every part of their lives: clinics, businesses, schools, workplaces, parks, and beyond.

But I want to be honest: when I was first approached to lead this work in Durham—forming what became Breastfeed Durham—I was overwhelmed. The Ten Steps felt like too much. Too big. Too hard. Too much work to ever get done.

And then I had a conversation that changed my life.

A national Black lactation advocate—one of the first people I spoke to on this journey—told me about her story. I remember asking her how she knew so much about the connection between Black maternal health, infant mortality, and lactation. She burst into tears in my arms and told me she had lost her first baby to SIDS. And when she got pregnant again, she started researching everything she could to prevent it from happening again. That’s when she discovered the role of breastfeeding in reducing SIDS. That’s when she became an advocate.

She looked at me and said, “We do better when we know better.”

That moment—that truth—is what lit the fire in me to begin this work. And it’s what continues to drive me.

What Happened with Duke Primary Care?

In March, we received an official message from Director of Population Health at Duke Primary Care Clinics in Durham County, stating that Duke Primary Care would not participate in our optional, non-evaluative survey designed to recognize clinics that support breastfeeding families. Every question was optional. Every answer had the potential to bring support and resources, not scrutiny or shame.

Duke Primary Care Clinics declined to participate.

To be clear: this is not a statement on every clinic, provider, or department within Duke Health. We have deep respect for many individual providers who have gone above and beyond. But Duke Primary Care’s leadership has chosen not to publicly engage in our local effort to make Durham a Breastfeeding Family Friendly Community. While Duke Primary Care has declined to participate in our survey at this time, they expressed interest in continuing informal collaboration and appreciated the resources available on our website. We’ve been invited to share community resources at an upcoming team meeting.

By declining, they have also declined to demonstrate alignment with:

- Step 5: Health care in the community is breastfeeding-friendly

- Duke Primary Care clinics have declined to participate in our survey, which is the first step toward receiving support and recognition. We’ve also heard that Duke Regional Hospital may not renew its Baby-Friendly Hospital designation, and that Duke University Hospital does not intend to pursue it. This step requires both hospital and outpatient settings to support breastfeeding through trained staff, patient education, and continuity of care.

- One of the key barriers we’ve identified is that labor and delivery nurses at Big Duke are not consistently trained in lactation support. This is deeply concerning, especially because Big Duke serves the families with the most medically complex pregnancies—the highest-risk moms and babies in our region. These are exactly the families who deserve access to skilled lactation care.We know, for example, that people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are more likely to face challenges establishing milk supply. They often need to induce lactation early, and may need more hands-on help postpartum. Without appropriately trained nurses, those opportunities for life-saving support are missed.Training is not optional. It’s essential. And the refusal to address this gap puts our most vulnerable families at risk.

- Step 7: The businesses and organizations in the community welcome breastfeeding families

- Duke clinics and offices should be visibly welcoming to nursing families—with signage, informed staff, and public affirmation. To date, Duke Primary Care has declined to participate in our Breastfeeding Welcome Here award, despite these being low-bar, optional recognitions.

- Step 8: Local businesses and healthcare clinics follow the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes

- At Duke, implementation of this step is inconsistent across clinics. We know that some Duke clinics—like Duke Family Medicine—are purchasing their own formula and are in compliance with the Code, actively avoiding corporate influence and marketing. Others are still displaying formula-related advertisements or distributing branded materials, which directly contradicts the Code. There is no clear or enforced system-wide policy at Duke to ensure alignment with these internationally recognized standards. When institutional consistency is lacking, families face unequal care—and some are harmed more than others. Participation in our survey would have allowed us to begin this conversation—but they’ve declined even to answer questions. Why?

- Step 9: The US Business Case for Breastfeeding is shared with employers to support lactating employees

- This includes Duke Health’s own responsibilities as an employer. Are lactating employees supported with protected pumping time and space? Are Duke’s internal policies aligned with federal law and best practices? Right now, there’s no way to know—because leadership will not officially engage.

We cannot recognize any healthcare system as breastfeeding-friendly if it refuses to even answer the question. While this means we cannot currently highlight Duke Primary Care clinics in Step 5 of the Ten Steps initiative, we’re hopeful that ongoing conversations and informal collaborations can lay the groundwork for future engagement.

This Is Bigger Than a Survey

This refusal comes just weeks before Black Maternal Health Week. It sends the message that, even now, in 2025, large institutions are still unwilling to publicly commit to the work of equity—especially when it involves being accountable to Black and Brown families.

But this isn’t the end of the story.

We still believe Duke Health can be a national leader in lactation equity. Let’s take the next step together. We know the providers and clinic staff are doing meaningful work. And we still hope that leadership will find the courage to join this community-wide effort—not through private conversations, but through public participation and shared standards.

What We Need Now

We need Duke Health—and all healthcare systems—to say yes to equity, to transparency, and to our communities.

We need we need Duke University Health Systems to commit to:

- Listening to families, especially Black families

- Aligning with evidence-based breastfeeding standards

- Working collaboratively with public health leaders and local advocates

- Participating in the 10 Steps initiative, starting with Step 5: Health Care is Breastfeeding Friendly

Let’s be clear: this is not about blame. It’s about the lives and well-being of our community.